Everyone has a favorite holiday, whether it entails presents, scary costumes, or sacrificial turkeys. But there are a number of holidays from the dustbin of history that our families may have celebrated in the past or have their roots in more ancient traditions. Here are a few forgotten holidays you may want to mark on your calendar for 2024.

Casimir Pulaski Day, first Monday of March

Written by Aysha Haq, Readers Advisory Librarian

Casimir Pulaski, born in Poland, fought in the American Revolution. Pulaski joined George Washington’s army after meeting with Benjamin Franklin in Paris. Pulaski was known to have saved Washington’s life and led a counterattack at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777. Pulaski was fatally wounded during the Siege of Savannah in 1779. To commemorate his service, Illinois Governor Jim Thompson signed a bill to create Casimir Pulaski Day in 1986. The holiday also honors the state’s large Polish population. It’s celebrated on the first Monday in March.

At the time, schools across the state were closed for the holiday, but starting in 1995, schools had the option of closing for Casimir Pulaski Day. This year, only 35% of schools in Illinois closed for the holiday. Since Casimir Pulaski Day is not a public holiday and government and public offices remain open, most people do not know about Pulaski Day. There are statues of Pulaski in Savannah, Georgia and in Washington, DC.

Von Steuben Day, September 17

Written by Brian Smallwood, Adult Services Librarian

Portrait of Baron von Steuben (circa 1786), by Joseph Wright, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Von Steuben Day is a holiday that celebrates the Prussian-born Baron Friedrich von Steuben. Born on September 17, Von Steuben is highly regarded as one of the most important German Americans ever. He is famous for offering his services to then-General George Washington in the American Revolutionary War. His training of the young American troops made victory against the British possible. Von Steuben Day is generally considered the German-American event of the year. Traditionally held on a weekend in mid-September, celebrations focus on parades where participants wear traditional costumes, including dirndls and lederhosen, to celebrate their heritage while marching, dancing and playing music.

While Von Steuben Day is celebrated in many cities all across the United States, including Chicago and Philadelphia, the largest crowds gather in New York City. Every year, on the third Saturday in September, German-Americans celebrate the Annual Steuben Parade on Fifth Avenue with an Oktoberfest-style beer fest complete with food and live music in Central Park. It has grown into one of the largest celebrations of German and German-American culture in the United States.

The first Steuben Parade was held in 1957 in the German neighborhood of Ridgewood Queens. In 1958, the parade was then moved to Yorkville, known then as Germantown, and lined up on 86th Street. 86th Street was once the heart of Little Germany and was affectionately called the “German Boulevard.” Over the years, it gained the city’s recognition and marched up Fifth Avenue, turning onto 86th St and marching across to First Avenue.

German-American Steuben Parade, New York (2013)

Today, the parade still marches up Fifth Avenue but now ends only at Fifth Avenue and 86th Street. It is led by cadets representing the German Language Club of the Military Academy of West Point, which General von Steuben founded. The three-hour parade is dominated by traditional German groups, spectacular colorful floats, marching bands, clubs and organizations from Germany, Switzerland and Austria, as well as the U.S. and Canada, wearing their traditional German costumes. The parade honors one or more Grand Marshals, either American citizens with a German background or German citizens with a special relationship to America.

Fun Fact: The Chicago Von Steuben Day Parade was featured in an iconic scene from the now classic 1986 film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off starring Matthew Broderick.

Von Steuben Day Parade from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

Find books about Baron von Steuben in our collection

Evacuation Day New York, November 25

Written by Christopher Halvorsen, Assistant Manager, Adult and Teen Services

New York, November 25, 1783. As the hated British fled the island of Manhattan, General George Washington marched his army to lower Manhattan to reclaim Fort George, which he lost to the British seven years earlier. However, the U.S. troops in the fort could not raise the Stars and Stripes because the British had nailed in the Union Jack and had greased the pole to prevent climbing it. However, John Van Arsdale, a young Sergeant from a New York company with cleats from a local hardware store, managed to climb the pole, rip down the Union Jack and hammer in the Stars and Stripes just as General George Washington was entering the fort.1

Thus began Evacuation Day, which was the biggest holiday in New York for the next 80 years. It was celebrated with fireworks, military drills, lavish dinners, recreations of Van Arsdale’s flagpole climb and flag-raising ceremonies often led by Van Arsdale’s descendants.2

However, the holiday began to decline in popularity as the people who were alive at that time began to die off. Also, competition from Thanksgiving, a national holiday created by Abraham Lincoln on October 3, 1863, and celebrated around the same time as Evacuation Day, cut into its popularity.3 Finally, World War I killed off all official celebrations as the British were now our allies in the war, and it was seen as unseemly to celebrate our victory over them. The last official Evacuation Day was celebrated in 1916.2

Oh, and there was also an Evacuation Day on March 17 for Massachusetts. But it didn’t have flagpole climbing celebrations.

Sources:

1. earlyamericanists.com/2014/11/25/the-story-of-evacuation-day/

2. untappedcities.com/2023/11/14/evacuation-day-new-york-citys-forgotten-november-holiday-2/

3. cc.com/video/qvkfcn/the-daily-show-with-jon-stewart-happy-evacuation-day

Repeal Day, December 5

Written by Debra Dudek, Adult and Teen Services Department Manager

December 5, 2023, marks the 90th anniversary of Repeal Day, a holiday that was widely celebrated in 1933. Why would the American public party hard in the middle of the depression? They were hoisting a glass to the end of Prohibition, a thirteen-year stretch from 1920 to 1933, which rendered commercial manufacture, sale and transportation of alcohol throughout the country illegal.

Prohibition swept in with the 18th Amendment and was swept out with the 21st Amendment. Was drinking alcohol during Prohibition illegal? No. People could still open a bottle of medicinal whiskey, sip on sacramental wine, or enjoy home-brewed beer and wine at home. The commercial production and transportation for personal consumption of alcohol was off-limits, which drove thirsty consumers to less than reputable avenues to acquire beer, gin, whiskey, bourbon, tequila and other boozy beverages. Organized crime grew in power and influence when they stepped in to supply consumers with what the government denied them.

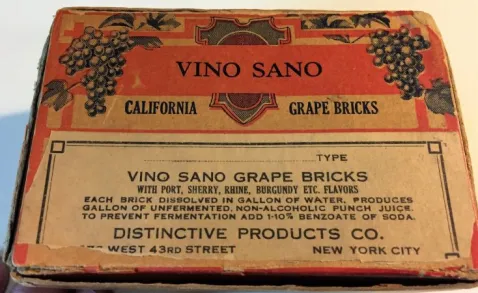

What was exempt from Prohibition? Hard cider, as well as other fruit-based alcoholic beverages. This was a lawful exemption to help farmers and rural families preserve their fruit crops. Wine companies saw this loophole and began selling grape bricks, which included clever little warnings and instructions on how NOT to make wine.

Vino Sano Grape Brick

Vino Sano Warning Label

Prohibition wasn’t an overnight act. There was a slow and steady progression of states banning the manufacture of commercial alcoholic beverages. The temperance movement had been peer pressuring local and state governments to pass prohibition laws since the 1840s with limited success. Chicago went dry in 1851 when a short-lived ban on the sale of alcohol was passed on a local level, which, due to public outcry, was repealed, and the men who had passed the measure were voted out of office.

Fifteen states passed prohibition laws in 1918 under the guise of a wartime measure, and by the time a constitutional amendment was on the table, only two states – Rhode Island and Connecticut – rejected the amendment.

Before the passing of the 18th Amendment, people had wildly different ideas of what was actually going to happen. Most people thought the amendment banned spirituous alcohol, but left wine and beer alone. While others interpreted the amendment as an overall decrease in sales of certain manufactured drinks, such as whiskey, bourbon and gin. But when people woke up on Thursday, January 1, 1920, to read all commercial alcohol was illegal, regret set in.

It was a lot like modern-day Brexit. Few people knew exactly what they were voting for. The most searched-for term the day after the election was ‘What is Brexit?’

Wayne Bidwell Wheeler, c. 1920

So why would a government give up a third of its taxable income and push millions of people into a lifestyle choice they didn’t agree with? Give credit to attorney, political organizer and party killjoy Wayne Wheeler. As the leader of the Anti-Saloon League, Wheeler developed a method of peer-pressuring politicians into supporting Prohibition by leveraging mass media, endorsing and financing opponents, blackmailing and threatening to end political careers with the power of his small moral minority. His hold on prohibition politics ended with his death in September 1927, making way for a majority-backed repeal movement to grow and flourish.

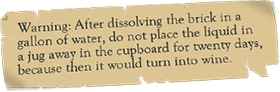

WONPR Vintage Liberty Bell Pin

While groups such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League consisted of politically active women, another group of equally passionate women created the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR). Founded in 1929 by Pauline Morton Sabin [PDF], WONPR had a single goal – repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Get alcohol money out of the pockets of organized crime and back into the coffers of local businesses and the federal government. America was scrapped for cash, and losing a third of its taxable income for almost a decade would have disastrous outcomes when the Great Depression upended the country. Prohibition repeal was not only a financial necessity, but it would also ensure thousands of Americans would have jobs and a steady income.

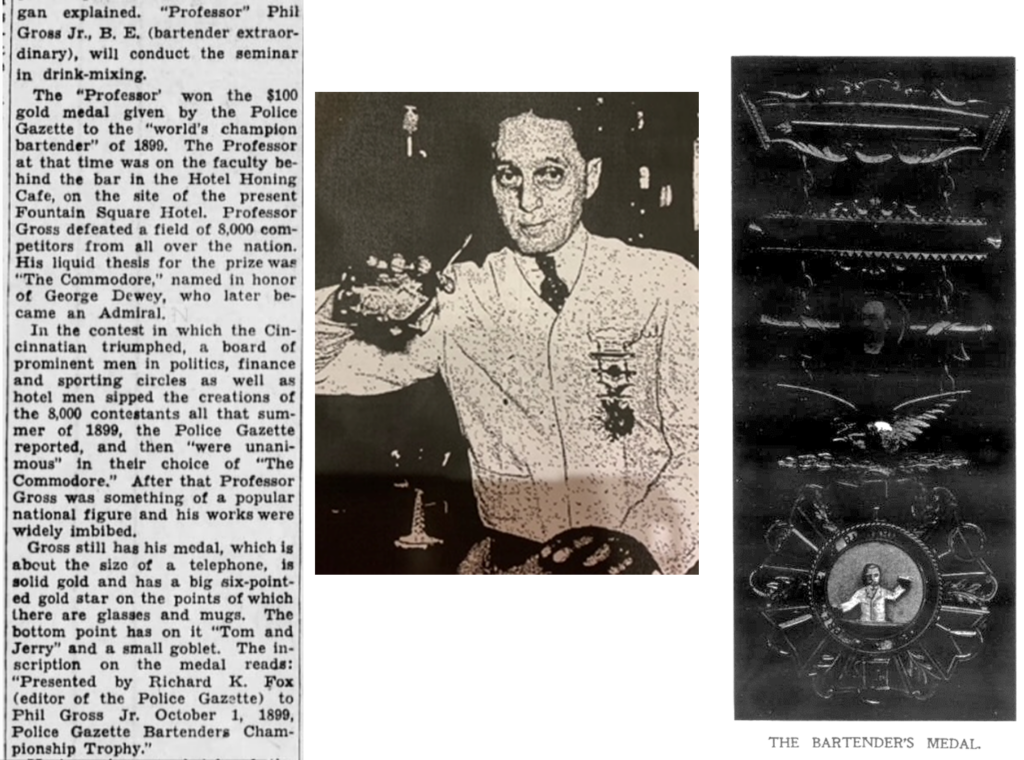

When the 21st Amendment was proposed on February 20, 1933, few people stood in its way. With the old 18th Amendment on its way out, enforcement of the law virtually ended, and bartenders, brewers, distillers, winemakers and other industry workers returned to their professions after a 13-year absence. One of whom was Phil Gross, Jr, the winner of the 1899 National Police Gazette Bartender Competition. A successful bartender at one of the top hotels in Cincinnati, Prohibition ended a successful career. He bounded between Wisconsin and Ohio holding various jobs for over a decade. He married, divorced and drifted through life unfulfilled. Phill was hired at a hotel in his hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1933 to give ‘demonstrations’ of his skills as a master mixologist. He was back at work even before Prohibition ended. The drinks were flowing again.

“Professor” Phil Gross c. 1933

(photo compliments of Molly Wellmann)

The Cincinnati Enquirer September 4, 1933

So, mark your calendar every December 5 for Repeal Day, a legacy of dubious and underhanded good intentions shaken up by a politically active vocal majority, which then served Uncle Sam with the tax money he desperately needed. What a country. Who wants a drink?

Learn More About Prohibition:

- Browse vintage cocktail books dating before, during and after Prohibition.

- Learn how the iconic Berghoff Restaurant survived Prohibition and obtained the first post-Prohibition liquor license in Chicago.

- Read 100 Years Later, Prohibition’s Legacy Remains by David Crary on PBS Newshour.

Books From Our Collection:

- Last Call at the Nightingale by Katharine Schellman

- Blind Tiger by Sandra Brown

- The Wicked City by Beatriz Williams

- The Bootlegger by Clive Cussler

- Al Capone’s Beer Wars by John J. Binder

What to Watch:

Saturnalia, December 17–23

Written by Jay Purrazzo, Adult and Teen Services Librarian

The Roman festival of Saturnalia was traditionally celebrated from December 17 to December 23 of the Julian Calendar. Dedicated to the god Saturn, it had many of the current hallmarks we are familiar with, such as gift giving, feasting and the closing of government offices, but is mainly known for the widespread chaos. With Jupiter temporarily deposed, the social order was overturned. The distinctions between enslaved person and master, man and woman, were thrown out as everyone ran riot, partied, gambled and drank endlessly without regard for social standing or class.

Its most well-known tradition during a gathering or party was the crowning of the King of the Saturnalia, who lorded over the festivities and was tasked with keeping things as silly as possible. Saturnalia and the King’s later title of “Lord of Misrule” have lived on in many different incarnations. The holiday has had several incarnations and has survived several attempts to quell the unruly spirit of the season.

While Christmas as we know it is no longer about drunk and disorderly conduct, at the right family gathering, bar, or shopping mall, it still is in spirit.

Further Readings: