Last year, I talked about a handful of graphic novels and animated features that were heavily inspired by Japanese animation. Like I said in that post, anime’s influence on media around the globe is impossible to understate, but that influence is more obvious in some media than others. So here’s another group of anime and manga-likes to check out.

Catwoman: Hunted

When talking about anime from places other than Japan, you’ll inevitably run into a lot of edge cases. The line between Japanese and American animation has never been all that clean, and that only becomes more true with the passage of time.

Japanese production companies have had a hand in popular North American cartoons, ranging from Rainbow Brite in the 1980s to Steven Universe in the 2010s. American companies, meanwhile, have invested in anime productions such as the second season of The Big O or the adaptation of Takashi Okazaki’s Afro Samurai.

As the borders between countries and cultures blur, so too does the line between anime and “anime-inspired.”

And so here we find ourselves with an animated feature produced and owned by Warner Brothers, directed by Shisuke Terasawa—whose key animations on Akira are just the start of an illustrious career in Japanese animation–and written by Greg Weisman, who boasts an almost equally long list of credits in American animation including Disney’s Gargoyles and Cartoon Network’s Young Justice.

This film, part of the DC heroes’ extensive list of animated features, sees Catwoman get pinched by Batwoman and Julia Pennyworth, a lesser-known Batman supporting character and Alfred Pennyworth’s daughter. Catwoman is offered amnesty for her crimes in exchange for helping to take down the crime organization Leviathan.

The highlight of this feature is the focus on these women. DC animated movies can sometimes forget that they have female characters other than Wonder Woman and Harley Quinn, so seeing respect paid to a trio of comic book women who have each been around for decades is a delight.

Equally delightful is Catwoman’s characterization. She’s having a blast flirting and thieving her way through this adventure, but the film also shows off her strong principles.

This isn’t the deepest story you’re ever going to see, but if you want to watch strong, sexy animated women take down bad guys, then this movie delivers. At a brisk 78 minutes, this fast-paced adventure will hold your attention with lovely character designs and some surprisingly impactful emotional moments.

Ultimate X-Men

Oh, hey, it’s another one of those edge cases.

In an effort to include more diversity in their respective line-ups, Marvel and DC Comics have spent the last few years reaching out to writers and artists outside of their usual circles, including a few artists from East Asia.

Written and drawn by Japanese artist Peach Momoko, the new Ultimate X-Men is, in essence, a Japanese manga, albeit published by an American company and formatted like an American comic book, i.e., to be read from left to right.

With a unique art style that can weave between beauty and horror in the blink of an eye, Peach Momoko has provided some of the most captivating illustrations in Marvel Comics history. Momoko is frequently recruited to create beautiful variant covers, and she has also been entrusted to reimagine Marvel superheroes in the Demon Days series of comics, also known as the “Momoko-verse.” Now, Momoko brings her talents to a new universe.

The Ultimate Universe branches off of the main continuity of Marvel Comics, following an alternate history in which the rise of superheroes was forcibly delayed. It would seem, however, that the rise of the X-Men is inevitable in any universe, as Hisako Ichiki’s mutant powers awaken and she forms a friendship with fellow mutant Mei Igarashi. History repeats itself as this new group of X-Men comes into conflict with other mutants who believe they are the next step in human evolution.

Hisako and Mei, going by the hero names Armor and Maystorm, make a great leading pair. Hisako is withdrawn and sullen after the loss of her friend, but still brave enough to face her fears. Mei, on the other hand, is outgoing and optimistic, seeing her newfound powers as a chance to be like her idol Wind-Rider.

The way our leads contrast perfectly sums up the tone of the book, which is equal parts charming and disturbing. Momoko incorporates elements of Japanese horror, drawing from the country’s extensive history of urban legends and folklore. Fans of the Japanese versions of Ring and Ju-on (AKA The Grudge) or the works of Junji Ito will want to give this book a look.

The cherry on top is that, with this being the start of a new series and a new continuity, Ultimate X-Men is highly accessible for new Marvel Comics readers.

Ultimate X-Men is a difficult read, dealing with matters of suicide, abuse and discrimination, but I found the experience highly rewarding. Momoko tells a deeply compelling story that has me eager for the next release. I recommend giving it a shot.

Aeon Flux

One of the reasons Americans became captivated by anime in the first place is the wider variety of genres available in comparison to American animation, which historically tends to focus on comedy and light action.

In the ’80s, anime on VHS offered the American audience the novelty of shockingly violent and sexually explicit cartoons. Many of these stories, such as Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira or Go Nagai’s Devilman, also offered compelling and cerebral stories alongside all the gore.

Then, in the ’90s, TV anime like Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon presented young audiences with high-stakes drama and challenging themes. That isn’t to say that American animation was devoid of compelling drama even in this time period. The Secret of Nimh is a moody fantasy adventure film with dark and evocative imagery, while Batman: The Animated Series is one of the most thoughtful meditations on the character of Bruce Wayne in his 80+ year history.

But these titles were still aimed at kids, and the success of those ultra-violent and often thought-provoking ’80s anime proved that there was an untapped market of teens and adults eager for cartoons to engage them on their level.

Enter Aeon Flux.

This avant-garde animated series originally aired on MTV’s Liquid Television in the early ’90s. It follows secret agent Aeon Flux from the anarchistic city of Monica as she infiltrates and sabotages the totalitarian city of Bregna, where she often comes to blows with her enemy and lover, Trevor Goodchild.

A highly experimental series, Aeon Flux (or Æon Flux) has a total of two spoken words in its first two seasons. It draws from Gnosticism, German expressionism, BDSM culture and the ligne claire (“clear line”) tradition of European comics, just to name a few of the numerous influences that make up this series. Aeon Flux is made up of a thousand niche concepts smashed together to create something surprisingly cohesive.

While Aeon Flux may fill the same niche as mature anime aimed at teens and adults, it is no mere copycat. There is nothing quite like this series, to the point that I find myself struggling to describe it further. It’s the sort of series you really need to see for yourself, so I highly recommend checking it out.

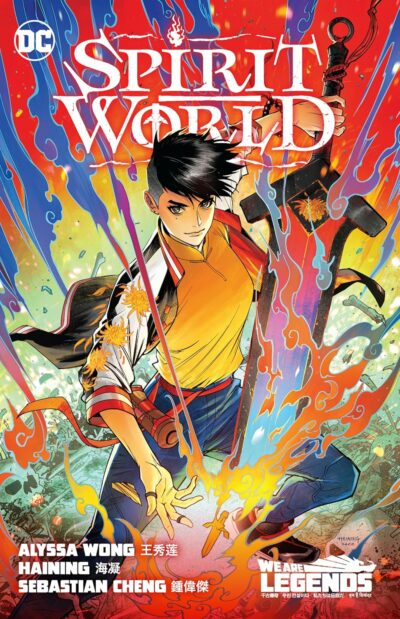

Spirit World

We talked about Marvel’s efforts to diversify its comics lineup; now, let’s finish up with DC’s. Spirit World is part of DC’s “We Are Legends” line of books, a trio of miniseries starring characters of Asian heritage. The other titles include The Vigil by Ram V and City Boy by Greg Pak.

The creative team behind Spirit World includes:

Alyssa Wong, an American writer famous for their speculative short fiction and poetry

Haining, a Taiwanese comic artist whose credits include DC Comics, Riot Games and BOOM! Stuidos

Sebastian Cheng, a Malaysian Chinese-American colorist with too many comic book and trading card game credits to list

Spirit World primarily focuses on new character Xanthe Zhou, a half-living young hero who can move between the land of the living and the Spirit World. Their powers are based on the Chinese tradition of burning paper effigies of objects to provide for deceased ancestors. Xanthe, being half-living and half-dead, can burn these effigies to make tools for themself–their favorite being a big ol’ Chinese broadsword.

After Batgirl Cassandra Cain becomes trapped in the Spirit World, Xanthe teams up with their chain-smoking British counterpart John Constantine to save Cass before hungry spirits can sink their teeth into her.

Wong provides an excellent and compelling story with a particularly moving detour from the action in which Xanthe is forced to confront their unsupportive family. As Xanthe’s creator, Wong does an excellent job of characterizing them as a charming, caring and clever individual. Wong does an equally great job with Cassandra–a character that not every comic book writer does justice to–and Constantine, who still feels like the same crass cynic he was under his creator Alan Moore in the ’80s, albeit with just enough edge shaved off to fit the PG-13 tone of the book.

Haining’s art and Cheng’s colors, however, steal the show and are the main reason I’m recommending this title. From the gorgeous, colorful backgrounds to the handsome character designs, nearly every page is a work of art. Big splash pages establishing the sights of the Spirit World give Haining room to flex her skills, while the smaller, character-focused moments show that she has equal talents for conveying emotion and expressions. There’s a subtle intensity to Cassandra’s shock at finding herself in the Spirit World, or Xanthe looking at the shrine to their past life that bears their deadname. Haining’s already phenomenal work is further enhanced by Cheng’s gorgeous coloring.

There are a few references to prior continuity, mostly in relation to Xanthe’s first appearance and some housekeeping regarding Cassandra’s tangled backstory, but otherwise this story is self-contained enough to recommend to readers who don’t normally follow DC Comics.