Hello and welcome to the final installment of my four-part Pride-month series: Speculative Fiction and (My) Pride, where I’ve been discussing how I’ve understood and related to Pride through the lens of diverse and inclusive media. The bulk of this series has dealt with Star Trek as a whole, as I believe the franchise makes a clear attempt to represent the infinite diversity in infinite combinations found in humankind. Trek has described a vision of an idealized future where anyone and everyone are not just tolerated, but they’re given the space to exist as their most authentic selves. It’s a positive and hopeful vision for the future, but it’s a world I didn’t find until well into adulthood. Where I found a place to belong, where I consistently find representations of LGBTQIA+ and queer lives, has always been in visions of a hopeless future, in dystopias and apocalypses.

Dystopian Literature: a form of speculative fiction that offers a vision of the future. Dystopias are societies in cataclysmic decline, with characters who battle environmental ruin, technological control, and government oppression.

I could get into the complicated reasons I believe LGBTQIA+ characters frequently appear in dystopias; suffice it to say that the core theme of many of these narratives revolves around dismantling unjust social systems to allow freedom for the people whose lives are impacted by tyranny or other unjust governmental control. Sound familiar? Below are two examples, one literary and one from television, where I found space to take pride in my identity. I could belong in these worlds—even if I wouldn’t want to.

The Locked Tomb Series by Tamsyn Muir

Genres: Fantasy; Speculative-fiction

First Publication: Gideon the Ninth (2019)

Other Publications: Gideon the Ninth, Harrow the Ninth, Nona the Ninth, Alecto the Ninth (forthcoming)

Eyan’s Rating: 5/5 overall

For Fans of: N.K. Jemison; the feeling when an author gaslights the reader

About

I. Love. This. Series.

There are a million reasons why, and you can be sure I’ll be writing a formal review of the final installment, Alecto the Ninth when it releases this October. For the purposes of this discussion, I want to highlight Muir’s use of gender, love and sexuality as distinct and important aspects of a person’s identity.

In interviews, Muir describes the series as being “very gender” because of how some characters can divorce themselves from their bodies. There are a lot of implications about souls, love, physicality, etc., in these books, but buried underneath a metric ton of plot that unfolds with a kind of creeping horror that you feel itching underneath your skin. The narrators, there is a different one in each book, aren’t exactly reliable, and the story is told in a back-and-forth manner that makes you question everything.

The core of this series, I’m asserting now, is about love that transcends. The way that various characters experience different types of love is profound. Most novels I’ve read, when introducing romance to a character, focus on one kind of love: sexual and physical, that overlaps with romantic. Muir expresses this kind of love, sure, but she also depicts love in incredibly unique and complex ways, which I find to be more reflective of the real human experience. The slow reveal of the series’ “villain” is also profound because you realize with each new morsel of information that this character started from a place of love and is now so far removed from any understanding of the emotion you don’t know whether to be frightened or heartbroken.

Muir’s books are incredibly successful with their diverse depictions of LGBTQIA+ characters in part because identity is not a part of the plot. Her world is as complex as our own, and her characters reflect myriad ways to represent and identify themselves with the natural grace of real-life people.

Start reading The Locked Tomb series

The Last of Us Season 1 Episode 3: “Long, Long Time”

Genres: Horror; Speculative-fiction; zombie apocalypses

First Publication: Adapted from the 2013 videogame The Last of Us

Other Publications: The Last of Us Part 1 (2013/2022) videogame; The Last of Us Part 2 (2020) videogame; The Last of Us: American Dreams graphic novel bonus content

Eyan’s Rating: 5/5 overall

For Fans of: Heartbreaking, bittersweet romances. If Leon the Professional was your favorite ’90s movie.

Check out a Roku and watch The Last of Us on Max (previously HBO Max).

About

Content Warning: Suicide, death

I will not go into a whole synopsis of The Last of Us as a franchise (that’s forthcoming). However, the story writing involved in this franchise is profound and deserves speaking about on a list of speculative fiction and Pride. You don’t need to know anything about the series to get the impact of the story; this episode is a complete narrative in its own right. The episode’s deployment in the development of the overarching plot and themes of The Last of Us is intentional, foreshadowing some intense choices that the series protagonists will have to make down the road, “Long, Long Time’s” power rests in its ability to tell a story about two people and their love.

Episode three in season one, “Long, Long Time,” departs the main chronological narrative, which had been following Joel and Ellie to witness the apocalypse through the character Bill’s perspective. Bill is a gruff loner, a doomsday prepper who is supposed to help the protagonists retrieve a truck battery.

In the game, there are subtle hints and nods to Bill’s life: he mentions a “partner” who got tired of Bill’s nasty attitude and leaves, there are several hand-written notes scattered around that players can find and read, and some of the background dialogue Bill speaks all work together to form this sad picture of a man who, though his survival skills kept him alive through a time when most of humanity perished, cannot compromise with the people around him. He is alone when players encounter him and alone when players leave again.

There is a poignant moment when the group finds a hanged skeleton with a suicide note. The skeleton was Bill’s partner Frank, who had left in search of a better life. However, shortly after leaving Bill, he was bitten by one of the zombie-like creatures infesting this world. Rather than succumb to the virus, he hangs himself. Bill is clearly emotional during this scene in the game: his voice cracks, he turns away from the body, and he returns to an almost exaggerated version of the gruff and unfeeling man he purports to be. For players of the game, this is what we expected with this third episode.

However, the show, written a decade later, takes a more intentional stance on Bill and Frank’s relationship, writing Frank into the narrative as a complete character in his own right. We see the relationship between the two men unfold over two decades as their slow dance toward love is revealed in a series of snapshots through time.

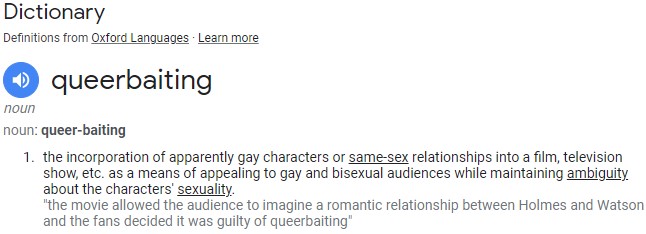

The episode is a touching and wonderful rendition of a love story told during harrowing times. Human emotions and entanglements don’t cease just because the world falls apart. The Last of Us is, at its core, a story about love and relationships and the distances we go to preserve those we care for, and that’s incredibly clear with this episode. What makes the Bill and Frank love story more touching is its rarity. For queer people, we’re used to subtle representation to the point of obscurity, often because writers/developers are afraid of negative pushback. While I clearly read the video game Bill as queer (and the writer/creator of the video game, Neil Druckmann, agrees), the vague details allow for the space to say “never mind” and reject the representation. This is so common in media that there’s even a term for it: queer baiting.

This is one of the major signs of inappropriate or inaccurate representation, and I find it far more often than I find positive examples. “Long, Long Time” does justice to the trope by making it explicitly clear from the first moment what the relationship between Frank and Bill is, without being cheesy or offensive. Additionally, they avoid the bury your gays trope, the other big flaw in representation, by giving agency and control to both men’s deaths.

Bill and Frank’s deaths were presented in a touching and profound way that allowed both men to choose their own endings with dignity and poise, not tragedy. Yes, the characters still die at the end of their story, but it was a complete story; their deaths are not plot points that serve as development for someone else. Bill says it better than I ever could:

This is not the tragic suicide at the end of the play. I’m old. I’m satisfied. And you were my purpose.

Excuse me while I go cry some more.

A Note on Safety:

For the first time in history, the Human Rights Campaign has declared a National State of Emergency for LGBTQIA+ people living in the USA.

The Human Rights Campaign has also joined the NAACP, the League of United Latin American Citizens, the Florida Immigrant Coalition and Equality Florida in issuing travel advisories warning LGBTQIA+ of the risks involved in visiting the state of Florida.

For all LGBTQIA+ people, the question of safety is paramount. Coming out or telling the people in your life that you belong to the community is, more often than not, met with the loss of friends, family and/or security. For transgender, gender-nonconforming, agender, nonbinary or even cisgender people whose physical appearance rejects social norms, questions of gender and identity come with complicated answers.

New legislation has appeared in many states that restrict access to necessary healthcare and makes it difficult for people like me to even use the restroom without fear of violent pushback. I speak about my transgender identity constantly and consistently because I am often the first openly visible transgender person that many people meet. Even though I absolutely do NOT represent the community as a whole, it is my assertation that in normalizing my life and struggles by making them visible to those around me, I am making subsequent generations of transgender people have an easier time.

We are here, we have always been here, and we are simply asking for an equitable space to be held for us. That our voices are listened to when we describe our own selves.

The next time you’re reading a book or watching a show, ask yourself if you feel represented in that narrative.