ShortHaus Cinema’s next featured director reveals an interesting dilemma. Despite being one of the most well-known names in Hollywood and beyond, George Lucas is one of the least prolific directors we’ve featured, only directing a scant six films, four of which are episodes 1–4 of Star Wars. Even so, he is a revered character in our cultural consciousness, hailed as one of the great directors who reshaped the Hollywood system, invented the modern blockbuster and advanced the technologies of digital filmmaking and sound design. Undoubtedly, he was hugely influential, but nowadays, Lucas is much less of a director and much more of a producer.

We choose to focus on individual directors for ShortHaus as a means of finding focus. Through one face, we can see how their career advanced and evolved (and how yours can, too!). But filmmaking is inherently a collaborative medium. Directors are the face of the film, but the best directors build up a team of trusted collaborators to bring their vision to life, something I touched on in The Art of Storyboarding. Ridley Scott and Akira Kurosawa had big ideas that they communicated effectively to their teams of set designers and lighting technicians to create the desired feel of the film. And, of course, there are the cinematographers, editors and sound mixers that all add their input along the way. Directors with too much power result in, well, the prequel trilogy.

If you’d like to learn more about George Lucas and his work, drop by ShortHaus Cinema’s next meeting this upcoming Tuesday, May 7, at 7 p.m. We’ll be looking at his student works and discussing how they impacted his later illustrious career as a director and more. Lucas’s feature films are all available within our DVD collection, and his short, Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1139 4EB, is available on Kanopy!

With all that being said, George Lucas is a fascinating character, and I thought I’d take some time to focus on his skills and influences as an editor, the part of filmmaking he always loved so much more than directing or scripting. So, let’s start at the beginning.

From Wheels to Reels

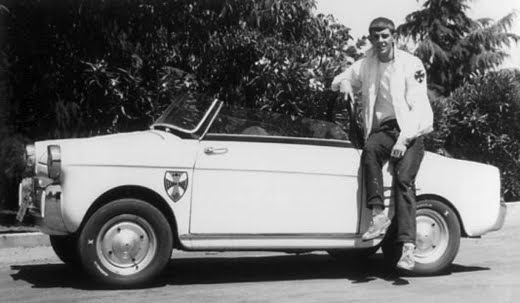

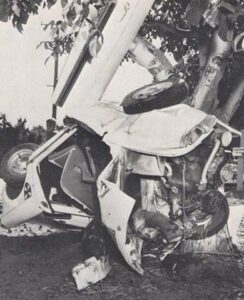

George Lucas originally wanted to be a race car driver. However, his perspective would immediately shift after a near-death experience that resulted in his car wrapping around a tree. After that harrowing experience, he decided to invest more in his schooling. He went to community college to study anthropology and sociology—subjects that genuinely interested him and would occasionally reoccur in all his films. Afterward, on a semi-whim, he studied cinematography at the University of Southern California.

a young Lucas and his Fiat

the inciting event

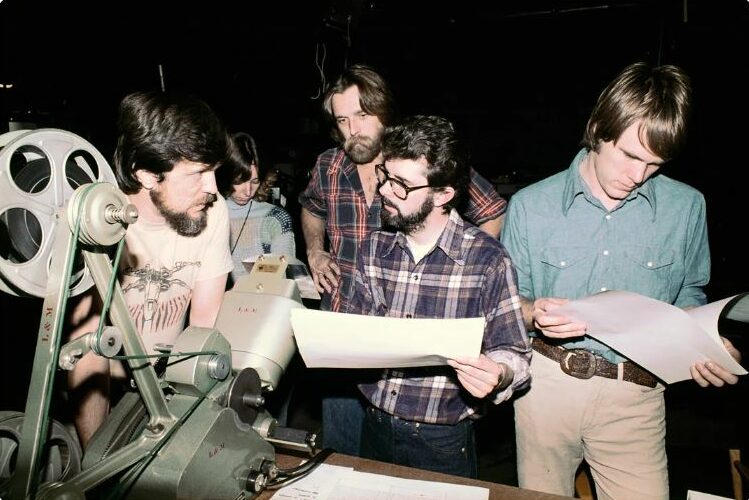

Compared to UCLA at the time, USC had a film program that was much more focused on the technical aspects of filmmaking. Students had to learn how to make a movie before ever getting a chance to write or direct one. This kind of teaching was perfect for Lucas, who loved learning how things worked. In his biography George Lucas: A Life, Brian Jay Jones compared the editing rooms to the car garages that Lucas spent his teenage years working in:

“The USC editing room looked like an auto shop class, with high ceilings, buzzing overhead lights, graffiti-covered walls, and equipment taking up most of the floor space. And the Moviola editing machines were Lucas’s kind of contraption, as comfortable for him as sliding behind the wheel of a car, with foot pedals to control the speed of the film, a hand brake, a variable motor switch, and a viewing screen the size of a rearview mirror.”

A young Lucas reviews storyboards for Star Wars over a Moviola alongside John Dykstra, Richard Edlund and Joe Johnston

Lucas’s love of cars would never completely disappear, and it’s on full display in the cruising culture of American Graffiti and the high-speed races of THX 1138 and Star Wars films. Even in his student days, the chase was always on his mind. His senior project would even be a return to form, where he used effective editing to convey the tension of man and his machine racing against the clock in 1:42:08 (1966).

from 1:42:08

from American Graffiti

from 1:42:08

Editing and Montage

USC’s technical-focused environment would be perfect for Lucas because he was much less interested in creating narrative films, especially not ones of the Hollywood blockbuster energy he would later become known for. Instead, he was much more excited by experimental filmmaking and tone poems. These works are much more evidently filmmaking as collages, as the images are often unrelated or barely tonally similar, so our minds have to make leaps to connect the disparate imagery and form new meanings.

A primary influence for this type of work was Arthur Lipsett, particularly the short 21-87 (1964), which is also known to be the original influence of the Force from Star Wars. 21-87 is an assemblage of scraps from the National Film Board of Canada cutting room floor, mixed with Lipsett’s street cinematography. Added to that diverse imagery is a constantly shifting audio track that sometimes offers reverent preaching, other times discordant tones and heavy breathing. The unrelated audio often causes slippage, where our mind struggles to find a connection and is engaged by the lack thereof. The final product shows a confusing look at modern life and culture in all of its layered glory.

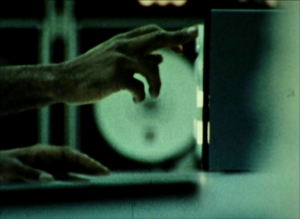

mechanical hands from a scrap of NFB documentary…

…juxtaposed against Lipsett’s candid street shot

Lucas’s version of this collage style of filmmaking can be seen clearly in his first film, Look at LIFE (1965). What was meant to be a basic camera exercise in learning how to zoom and pan on an animation camera, Lucas elevated from an assignment to a short film. He shot pages from Look and Life magazines and added music and dialogue tracks. Even at this early point, Lucas knew the importance of sound and perfectly synced his cuts to the percussive beats of the music. It’s only a minute long, but the simple sequence of images is evocative, sometimes slowly zooming on a painful image, other times panning quickly to mimic the motion of an anxious scene. Altogether, it reveals the simple magic of editing: the pacing and sequencing of images, when carefully orchestrated, can elicit emotions and connect to viewers in exciting ways.

romantic moments offer brief respite from the flood of violent imagery

the last shot of Look at LIFE slowly zooms in on this harrowing image

Lucas made several other student films that built upon these editing skills. As he shifted genres and experimented, he found ways to create tension or linger and play with tones, jazz, hazy reflections and the strange poetry of E. E. Cummings. Freiheit (1966) is relatively simple in scope, depicting a chase through the woods.

In its first half, the cutting is frenetic, quickly panning across the landscape and following the clumsy running of a man, cutting to his feet, running through a puddle, then cutting right back up again to his wildly pumping arms. Then it slows; he catches a breath, panting, and sees his objective: the border. The pan across the landscape is slow and deliberate, his eye searching carefully. Then he makes a break for it, and Lucas drops it into slow motion. For the 26 glorious seconds, it seems as if this man might make his goal.

from Freiheit

Then, BAM, choppy cuts of still frames screaming in agony from a gunshot wound. Suddenly audio of men and women defining freedom starts playing. The wounded man tries to crawl, but his attacker steps in front of him, and we zoom out on a still of the guard standing over his dead body, the echoes of freedom still ringing out. It’s simple, sub-three minutes, yet very effective. Lucas adds magnitude by tying the film to the current events of occupied Germany, a blue tint representing the cold reality of a new type of fascism that Lutz Dammbeck, previously featured by ShortHaus in January, would be all too familiar with.

Walter Murch and the Beginnings of THX 1138

Walter Murch was a fellow USC student with a similar passion for editing. So much so that he would go on to win three Academy Awards for his sound mixing and editing work on Apocalypse Now (1979) and The English Patient (1996). He would also write a fundamental text on editing, In the Blink of an Eye (1995). Murch would also favor the collaging aspect of filmmaking. In a 2015 interview, he said:

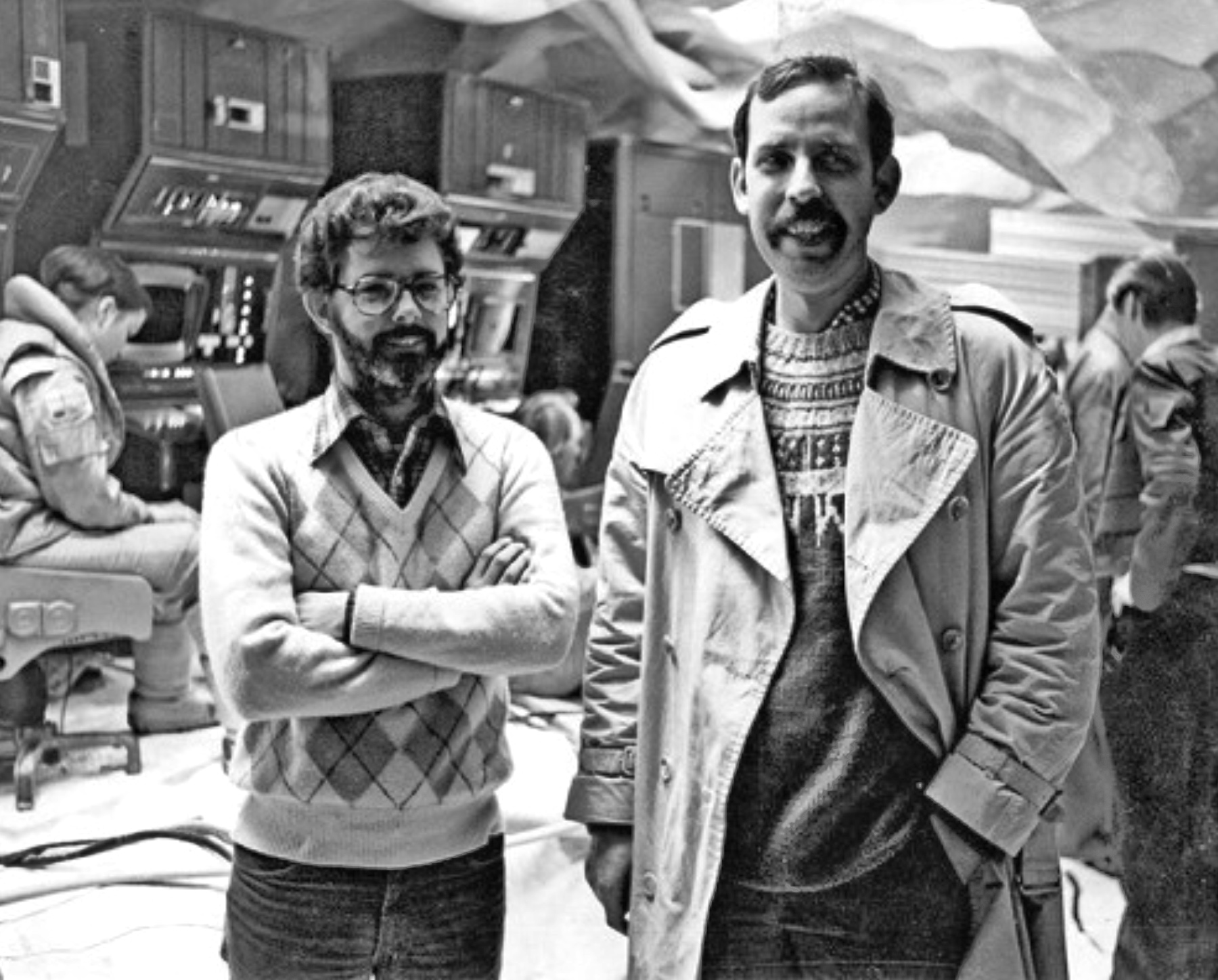

Lucas and Murch

“I wish we used the same word for editing that we use in Romance languages—French, Spanish, Italian—montage, which means to build, to put something together… In a real sense, those of us who put images together are doing a kind of metaphysical plumbing—making the ideas and the emotions flow as effectively and as quickly as possible, without any blockage or spillage.”

After graduation, Lucas returned to USC to teach filmmaking to Navy students, seeing it as an opportunity to create his film with the abundant military resources. As for a subject in this new film, Lucas wanted to bring the chase of Freiheit to an abstract level. He collaborated with Murch and fellow student Matthew Robbins to develop the story of a man running while being pursued through monitor screens, further disconnecting this subject from his world. Murch wouldn’t assist with the short film, but he would return as a writer on the feature-length adaptation after Lucas struggled with the script for months.

fleeing through empty airports

THX 1138 seen through the monitor of andorid police

military pursuit filtered through mechanical buttons

The short film Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB (1967) made very good use of its resources. The empty airports and UCLA parking garage serve well as an empty void of a dystopian city, while the USC computer lab and its wall of tech give a retro-future vibe. All the characters talk in repetitive bureaucratic, technical speak and only pursue the escapee through computer screens.

Their first “observational contact” with THX 1138 4EB is a particularly evocative image, just one long shot of a blue flickering monitor and security footage of an empty hallway. Then, slowly, an abstract form begins shifting at the center of the screen. It’s too abstract to decipher until suddenly it clicks: we are looking at a man running straight toward the camera, arms pumping as he runs as hard as he can.

a chilling visual

It’s chilling, and the rest of the film carries on that strange, estranged feeling. Everything is disconnected, and this world is empty of empathy. When the man does escape to the surface, the militaristic force declares him dead while we watch him run free.

The World of Worldizing

The short would use sound effectively for its budget, but Walter Murch would only expand on that when mixing for the feature that would be THX 1138 (1971). Much influence for the sound design would come again from Arthur Lipsett, as Murch described in a 2005 Wired article, Life After Darth:

“When George saw 21-87, a lightbulb went off. One of the things we clearly wanted to do in THX was to make a film where the sound and the pictures were free-floating. Occasionally, they would link up in a literal way, but there would also be long sections where the two of them would wander off, and it would stretch the audience’s mind to try to figure out the connection.”

THX 1138 isn’t emotionally resonant, but where it succeeds is alienation: its set designs are cold and sterile; its plot is simple yet confusing; its dialogue is wooden and full of nonsense psychobabble. It all adds to this dissociative quality inherent in a mass-sedated world. Murch’s sound contributes a lot to the dissociative feeling. The tones of mechanical beeps are layered with human voices disintegrated by intercom speakers, only ever heard through mechanical reinterpretation. Even when speaking face to face, the voices feel far away, like they’re constantly bouncing around their sterile white walls.

THX 1138 is disconnected even from his labor, using mechanical hands to build the android police

the feature film is more often characterized by vast, white, empty spaces

Murch accomplishes this through his technique of worldizing, where he creates atmospheric tones by playing a master track in a large space, like a gymnasium, and uses microphones placed at opposite ends to pick up all the echoey tones of the space. Or, he speeds a track up at four times its speed, records it on a second machine, and then plays it back slowed down.

even two figures speaking closely in a smaller room sound like they’re miles away

Somehow, this analog process quadruples the sound of the space. Although plenty of digital plugins can replicate these techniques nowadays, it’s fascinating to hear how they were developed and understand how to use them effectively in your work.

Worldizing made THX 1138 sound hollow and lifeless, but it also bloomed life into American Graffiti. Murch took that same tactic and rerecorded the soundtrack—which was an entire radio show performed by Wolfman Jack complete with a loaded forty-three-song soundtrack—and played it back across Lucas’s lawn to get an echoey track full of reverberation, movement and environmental sounds. Though that soundtrack could have easily felt like a jukebox jam, the songs only come to the forefront of the mix at key moments and transitionary places.

For the bulk of the runtime, Murch folds them into the mix by layering in his rerecorded track, allowing the music to sink back into the background. Dialogue floats to the top of the mix, or the sound just bounces around the scene, jumping from one car to the next, embedding us in the world of this late-night cruising in Lucas’s hometown of Modesto.

Wolfman Jack in the middle of his radio broadcast

Contemporary pop films could certainly take note and let their loaded soundtracks sit more diegetic within the world.

The Heart of Editing

In his book In the Blink of an Eye, Walter Murch outlines the criteria for a good editing cut and gives each criterion a percentage value for its level of importance:

- it is true to the emotion of the moment [51%]

- it advances the story [23%]

- it occurs at a moment that is rhythmically interesting and ‘right’ [10%]

- it acknowledges what you might call call ‘eye-trace’ [7%]

- it respects ‘planarity’ [5%]

- and it respects the three-dimensional continuity of the actual space [4%]

Though visual coherence and continuity are important, they’re nowhere near as valuable as the emotional resonance or story advancement of a scene. Marcia Lucas understood this philosophy well, and it is often considered the heart of George Lucas’s films. Marcia and George both had a deep love for editing when they met while working as assistant editors of Verna Fields in 1967. It was probably the only thing they truly had in common, as everyone was surprised by their matchup.

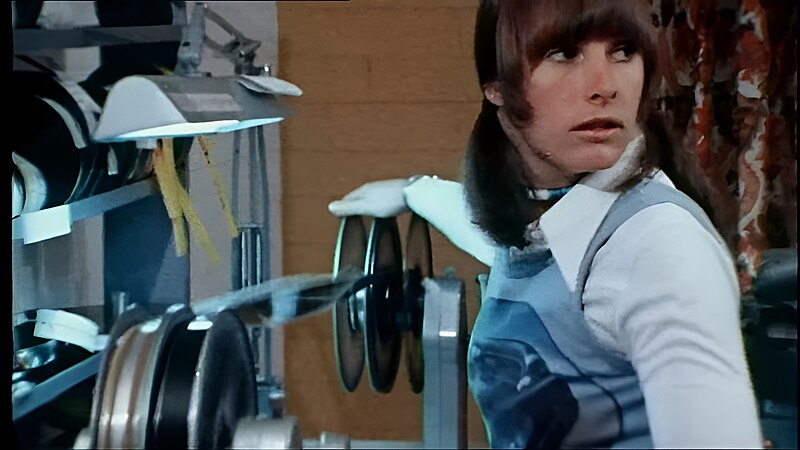

Marcia Lucas at work

Marcia knew a film needed heart to work. Though she edited THX 1138 side by side with George, she wasn’t given much executive power in the decision-making process, and most of her ideas were shut down. As a result, the film remains heartless, and she voiced her opinions on it. In contrast, George Lucas wasn’t given as much authority in the editing of American Graffiti, so Verna Fields and Marcia Lucas were able to edit the film to their own standards. George has already decided that it would be a much different type of film, but his editing choices always focus first on the visuals and second on the character dynamics. In that Life After Darth article, he said:

“The music and the visuals are where the story’s being told. It’s one of the reasons the films can be understood by such a wide range of age groups and cultural groups. I started out doing visual films – tone poems – and I move very much in that direction. I still have the actors doing their bit, and there’s still dialog giving you key information. But if you don’t have that information, it still works.”

It’s thanks to Marcia Lucas that there is still so much warmth in Star Wars. Without this, it might quickly veer into the territory of THX’s cold labyrinth. According to Mark Hamill (who also added to the films by changing lines of dialogue): “I know for a fact that Marcia Lucas was responsible for convincing him to keep that little “kiss for luck” before Carrie [Fisher] and I swing across the chasm in the first film.” That and many more moments offer much-needed warmth and levity in what could easily be just a singular power fantasy.

Marcia was also singlehandedly responsible for the climactic battle and Death Star trench run. Brian Jay Jones described in his book that “the effects footage was edited together so carefully and seamlessly with the live action shots that the technicalities [lack of actual ships, continuity errors] hardly mattered,” yet “it is always easy to tell what is going on; in several places, she made the editorial decisions to clarify the story and speed things up even more.” Under her careful eye, the chaos of war and production is carefully stitched together in a perfect high-stakes battle. And by simplifying the fighting, she could elevate the emotional beats of this pivotal scene.

Deus ex Millennium Falcon

In The Secret History of Star Wars, Micheal Kaminski notes, “She [Marcia] warned George, ‘If the audience doesn’t cheer when Han Solo comes in at the last second in the Millennium Falcon to help Luke when he’s being chased by Darth Vader, the picture doesn’t work.'”

It’s no wonder only one of the Lucas’ earned an Academy Award, and it wasn’t George.

Even so, only one of their names exists widely in public consciousness. Though Marcia would work on films like Taxi Driver (1976) and New York, New York (1977), most of her career was limited to assisting her husband on his projects. She would ask George for a divorce in 1982, and he would have her wait until the release of the Return of the Jedi to go public with the information.

Beyond his director credits, George Lucas has made waves with his productions and companies. As inspired as he was by Kurosawa, it is sweet that he got to turn around and produce the international release of Kagemusha (1980). He would also go on to lend the services of Industrial Light and Magic to Kurosawa for Dreams (1990), whose effects I raved about in Filmmaking as Collage. He would also work closely with Jim Henson on various projects, including helping to write and produce Labyrinth (1986). Whether it be as an editor, director, or producer, George Lucas has left his mark on the world of filmmaking.

Learn More

Editing is a huge part of filmmaking, and nowadays, it’s easier than ever with digital software like Adobe Premiere and DaVinci Resolve. Studio 300 offers these programs and more at your disposal in our digital media lab. You can also check out cameras, lighting and audio equipment to make your own movies. Online, you can access hundreds of tutorials on editing and filmmaking from LinkedIn Learning with just your library card.

If you’d like to learn more about George Lucas and his work, drop by ShortHaus Cinema’s next meeting this upcoming Tuesday, May 7, at 7 p.m. We’ll be looking at his student works and discussing how they impacted his later illustrious career as a director and more. Lucas’s feature films are all available within our DVD collection, and his short, Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1139 4EB, is available on Kanopy!