ShortHaus Cinema has featured many artists-turned-directors, but January’s featured director, Lutz Dammbeck, has remained firmly in the artist camp. His artistic practice includes drawing, painting, animation, collage, conceptual art, installations, research and documentary filmmaking. He is certainly the most avant-garde director to be featured by ShortHaus thus far, truly pushing our “Haus” namesake as he takes inspiration from Bauhaus and other early 20th century movements.

A Simple Start in Animation

Initially, when I dove into Dammbeck’s work, I was pleasantly disturbed by his lovely little animated shorts. The beautiful animations we’re used to seeing from the likes of Disney, Pixar and DreamWorks require teams and teams of people working together.

Searching for a topic to write on for this blog series, I thought I’d compare his work to Jim Henson, our last featured director, and take the time to talk about the simpler animation techniques used by smaller creators. Animation done by individuals takes a long long time, stays within a short duration and/or uses fewer frames so the end result is jerkier and less fluid. The comparison went a little something like this:

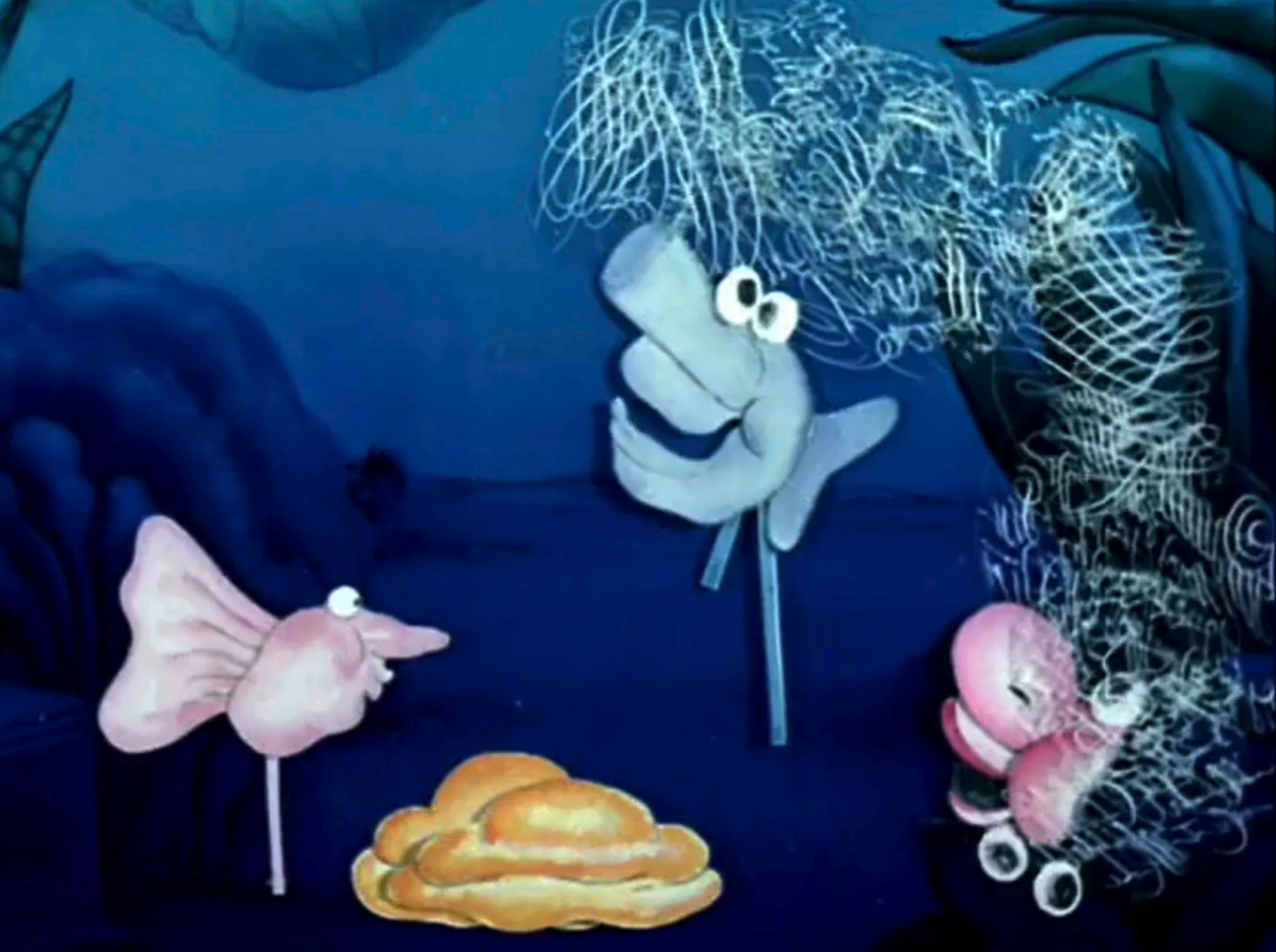

from The Moon (Der Mund), 1975

Henson v Dammbeck

Before puppetry became Henson’s primary focus, he liked to dabble in different techniques to make moving images. In the decade before the Muppets got their own show, he even considered himself an experimental filmmaker, creating an Oscar-nominated short and toying with big ideas to open a club where short films would be playing on screens and projected onto dancers.

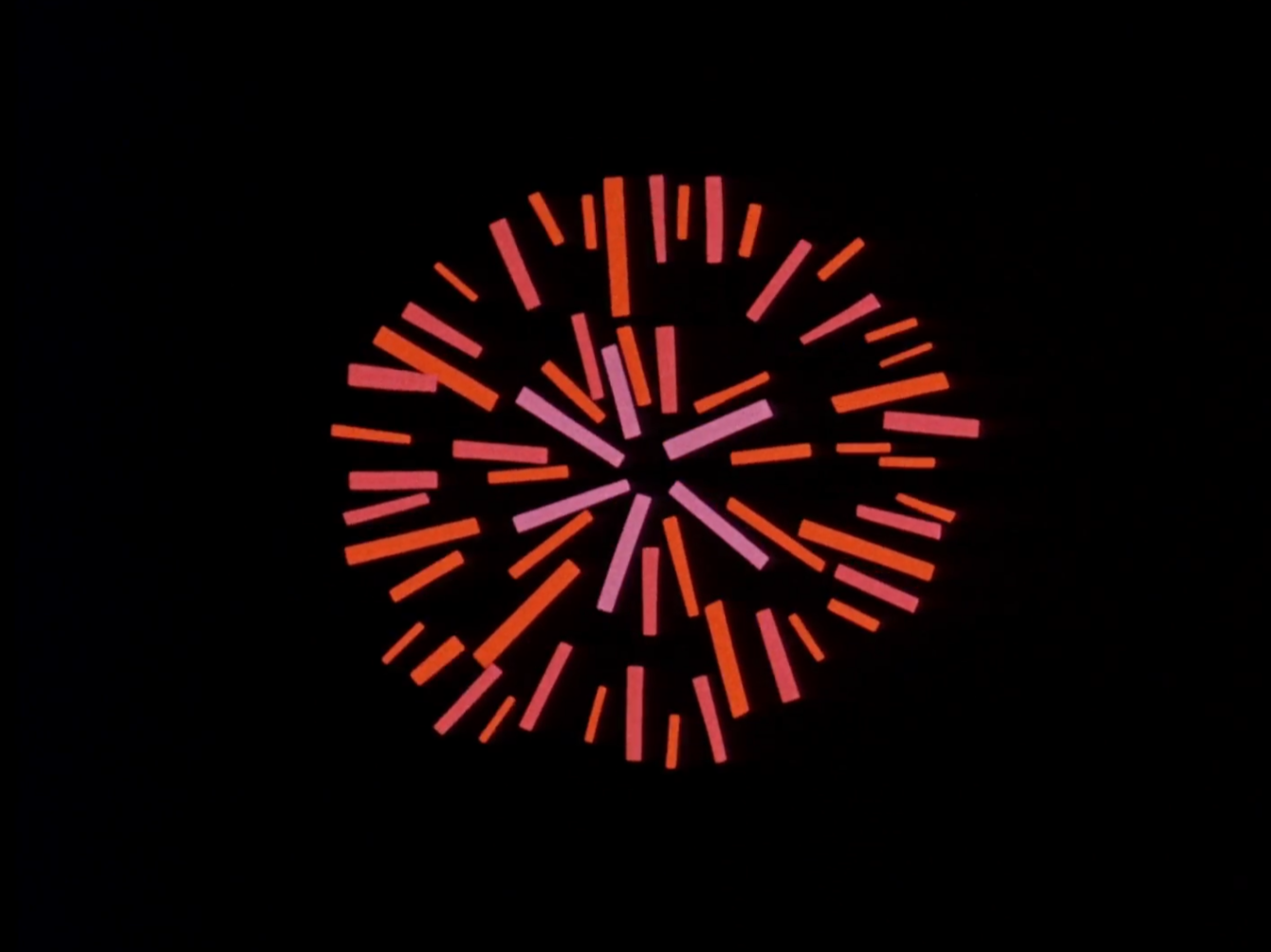

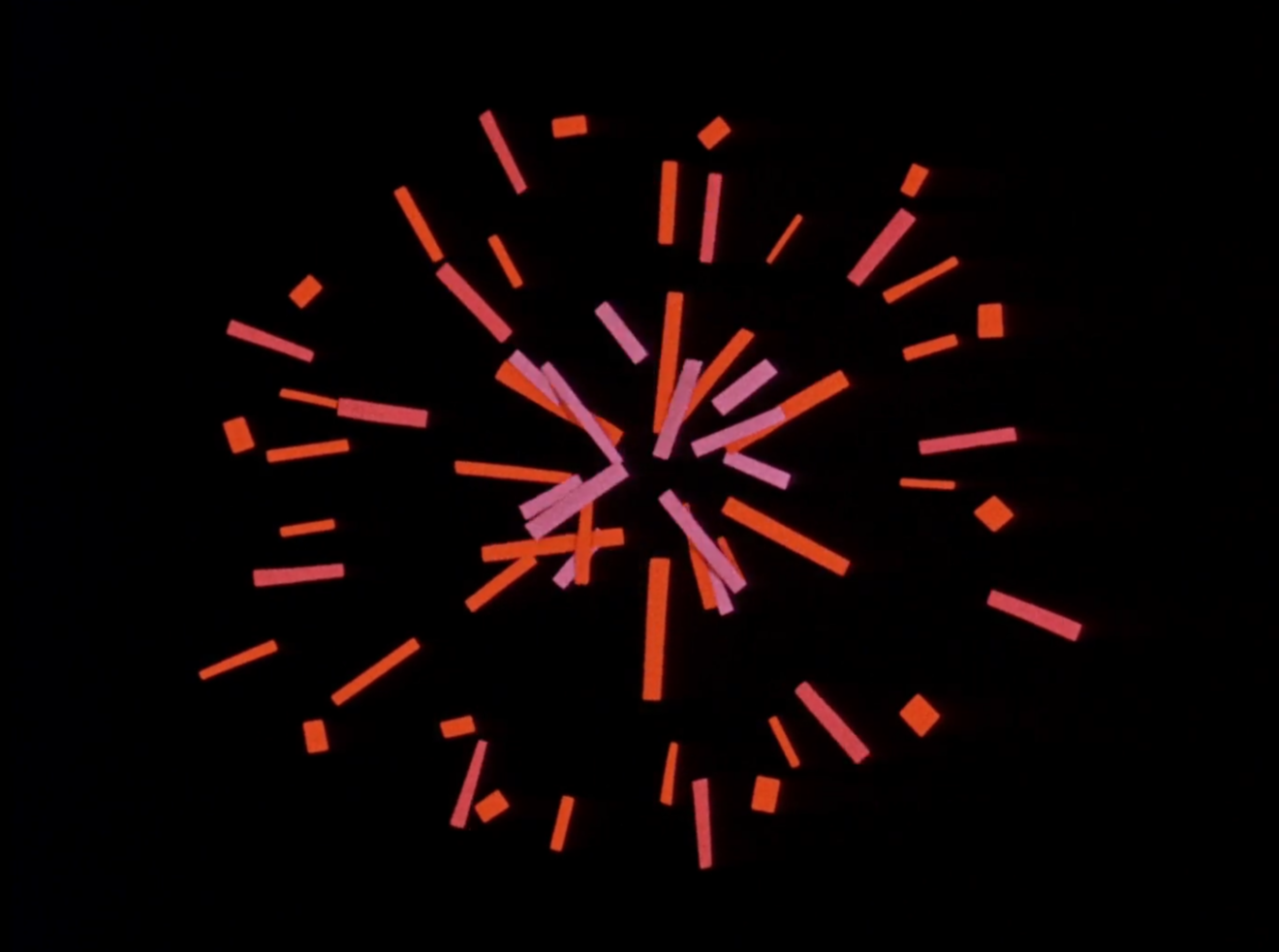

from Drums West, 1961

a few frames later, those paper scraps appear to burst out like a firework

As I discussed in Jim Henson: The Lost Art of Puppetry, abstract forms, like those of the Muppets, are more capable of coming alive through an actor’s performance because their simple features are more expressive. Similarly, Henson’s paper-cut animations in Drum’s West (1961) built on the simplest of forms—basic circles and rectangles cut from colorful paper—but it was how those scraps moved that gave them life. With stop-motion animation, he carefully shifted the forms and photographed each frame. He synched those images to the upbeat tempo of lively jazz music. As slow and tedious as the process was, the final result saw the forms dancing playfully across the screen to the beat, and he would use this technique again in his aforementioned Oscar-nominated Time Piece (1965).

from Cat and Mouse, 1961. The green-eyed cat lurks in the shadows, ready to pounce. The animals are drawn simply in white contour, yet remain expressive in their movements.

Henson’s hand-drawn animations were similarly playful. Cat and Mouse (1961) is simple, depicting, as its name suggests, a cat hunting a mouse. Each frame is painted by hand in a broad, abstract style. The movements are a little stiff from the lack of in-betweens (keyframes mark key movements and poses, while in-betweens help to transition between key gestures and expressions), but overall the creatures bounce around and are full of life (that is, until one is not so full of life as it becomes the cat’s meal).

Lutz Dammbeck also uses hand-drawn animations in his work, but his movements are far stiffer than Henson’s. The background is a gradient wash of watercolor. The only movement comes from the characters and the key environmental elements they interact with: flowers, grass, dripping goo, etc. The character movement is stiff and repetitive, often reusing the same frames. Other times movement is almost entirely lacking, as one pose is faded into the next, giving a very basic understanding of the choreography of each scene.

from The Discovery, 1983. The background remains still while only the petal the bee bounces on is animated with its movement.

The bee must wake the grasses every morning. Again, only the bee and the single blade of glass it holds are animated in the still environment.

from Einmart, 1981. The texture of the paper can be seen in the background and on the shading of the figure.

Rather than focusing on kineticism, Dammbeck creates textured worlds focused on materiality. Each character is carefully colored and shaded. Trees are drawn with wobbly pencil marks. The texture of the paper reveals itself in the way it holds the color of careful shading. Even the wash of watercolor is varied as the pigment unevenly absorbed and dried into the tactile medium. Line and texture take precedence over easily animated forms.

But why is that the focus of Dammbeck’s animated work? I was going to ascribe it to some inherent German artistic quality. A Germanness that dates back to the Northern Renaissance, where the focus was on carefully rendering the surface textures of symbolic objects. This is in contrast to the Italian Renaissance’s scientific representation of life with the use of linear perspective, atmospheric perspective and the camera obscura.

from Tailor of Ulm, 1979. Inspired by Bertolt Brecht, strange figures indistinguishable from one another dance in goo and praise the ruling bishop

But then I dug deeper into Dammbeck’s body of work, and I realized just how important German art history was to his entire oeuvre.

German Art History

Lutz Dammbeck was born in Leipzig in 1948. In this postwar Germany, fascism was recently eradicated, and would remain so under the careful watch of the allied powers. In the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) this meant the rapid dissemination of communism by the Soviets. In the name of anti-fascism, a new totalitarian government took control, and thus a new artistic standard had to be formed.

A rich art history had grown and adapted since the Northern Renaissance. German art still focused on beautifully crafted surface textures and poetic symbolism, a hidden poetry within dense, vivid visuals.

Ludwig Meidner, Apocalyptic Landscape (Apokalyptpische Landschaft), 1912. Dynamic diagonal movement and broad textured brushstrokes characterize expressionism.

This carried on into the German expressionist painting and film movements of the early 20th Century. Freudian psychology invited artists to focus on interiority, represented by loud, gestural marks rather than rendering an outer reality. This would have been the backdrop Dammbeck began his artistic career in, if a fascist army hadn’t marched through the art world and destroyed expressive forms in the name of protecting the populace from “degenerate art.”

The Soviet’s desire to rediscover German artistic traditions after the war was a noble one, but the communist rule in East Germany called for “a straightforward realism, accessible to the masses, as the alternative to rootless Western modernity.” Rather than building off the rediscovery of former traditions (expressionism, surrealism, Dadaism) the “new” German style would return to the style of the Renaissance, halting their German art history at Albrecht Dürer (not so coincidentally, Nazi art standards also revered Dürer for his adherence to naturalism and draftsmanship and his importing of classical Greek figures from his travels to Italy). And so, “The Soviet wish is the German communists’ command. They sacrifice their own roots and traditions to Socialist Realism.”

Albrecht Dürer. Self-Portrait at the Age of Twenty Eight. 1500. Notice the delicate rendering of hair and fur, the delicate gesture, but the lack of environment to give perspective.

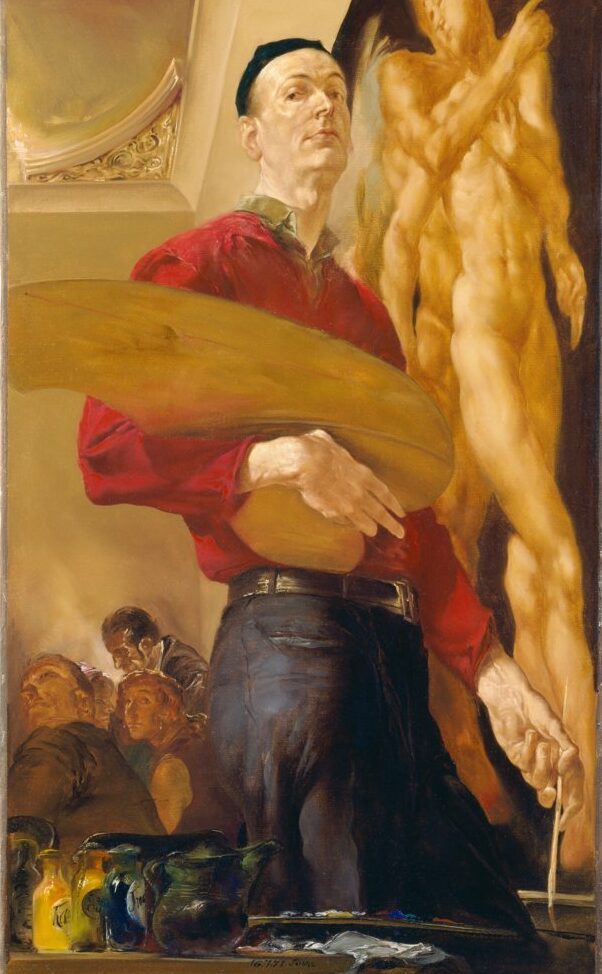

Werner Tübke, Selbstbildnis mit Palette (Self-portrait with Palette), 1971. Tübke was a professor at Leipzig Academy and a significant artist working in the Socialist Realism style

Those quotes are from Dammbeck’s narration in his documentary Dürer’s Heirs (1996), where he describes how the Leipzig Academy for Graphic Art and Book Design became the center of this Socialist Realism style. Dammbeck himself studied at this school from 1965–1972. It was there he began playing with animation and made the connections to create state-sponsored films. The aforementioned shorts were all created for the state-owned film studio, the DEFA (Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft).

However, when Dammbeck wanted to move beyond animation, finding influence in all the pre-war isms, his art was deemed too revolutionary. He and his peers could no longer find support for their art in state-sponsored institutions and had to hold a guerilla exhibition of their work in 1984, creating the First (and only) Leipzig Autumn Salon. When the state made it clear such an event could not happen again, Dammbeck moved his family to Hamburg in West Germany to continue his artistic practice without restriction.

Filmmaking as Collage, Part 2

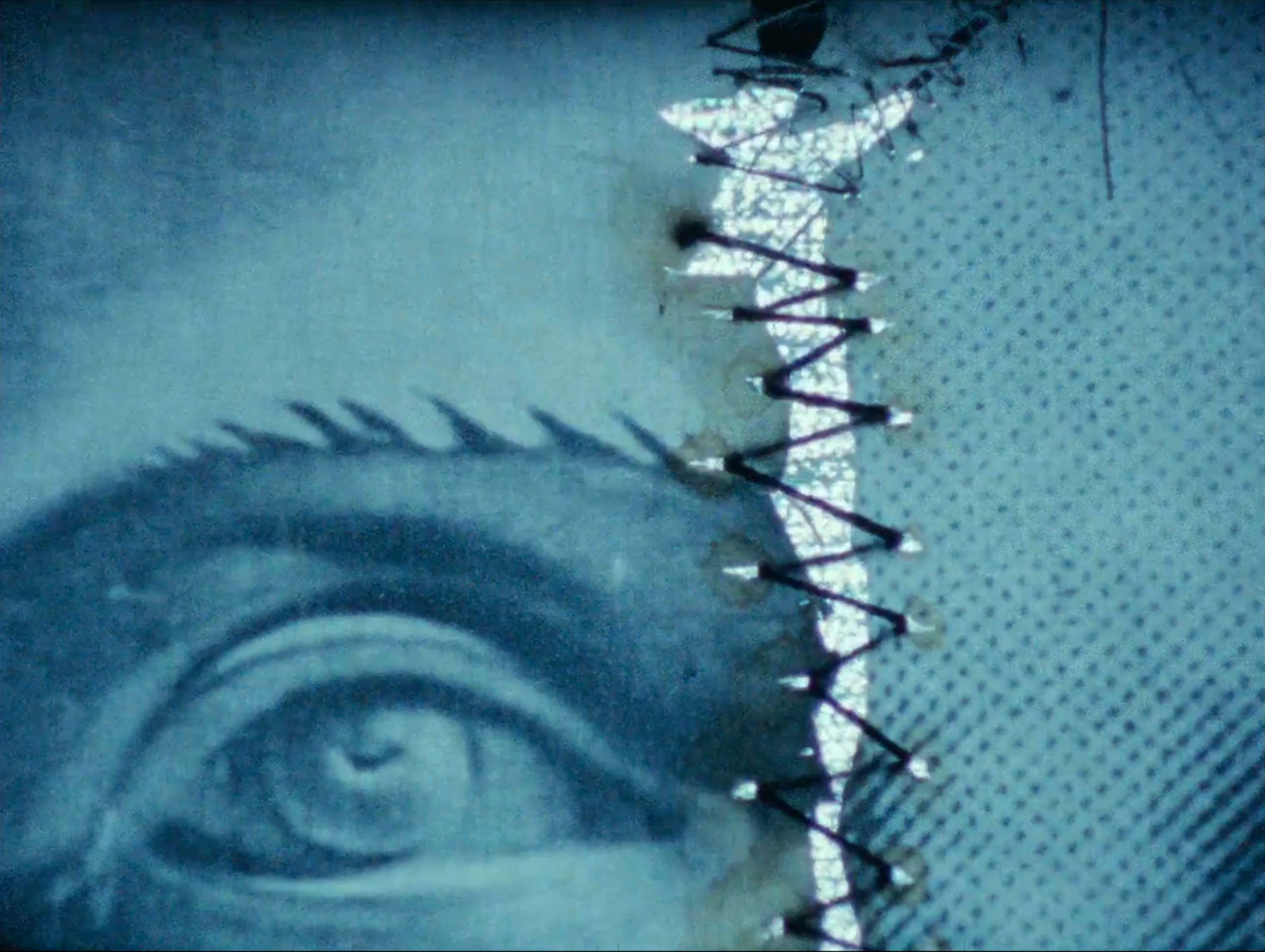

In West Germany, Lutz Dammbeck was able to build on his previously rejected Cave of Hercules (Herakles Höhle) (1990) concept and prove himself as a collage artist after my own heart. He was in good company with Dada collage artists like Hannah Hoch, who I mentioned in my Filmmaking as Collage blog. Dammbeck’s early collages were very tactile and combined photographs and images of grecian busts, torn and cut and sewn together in Frankenstinian ways with thick twine, then painted over with thick, gestural black and white paint.

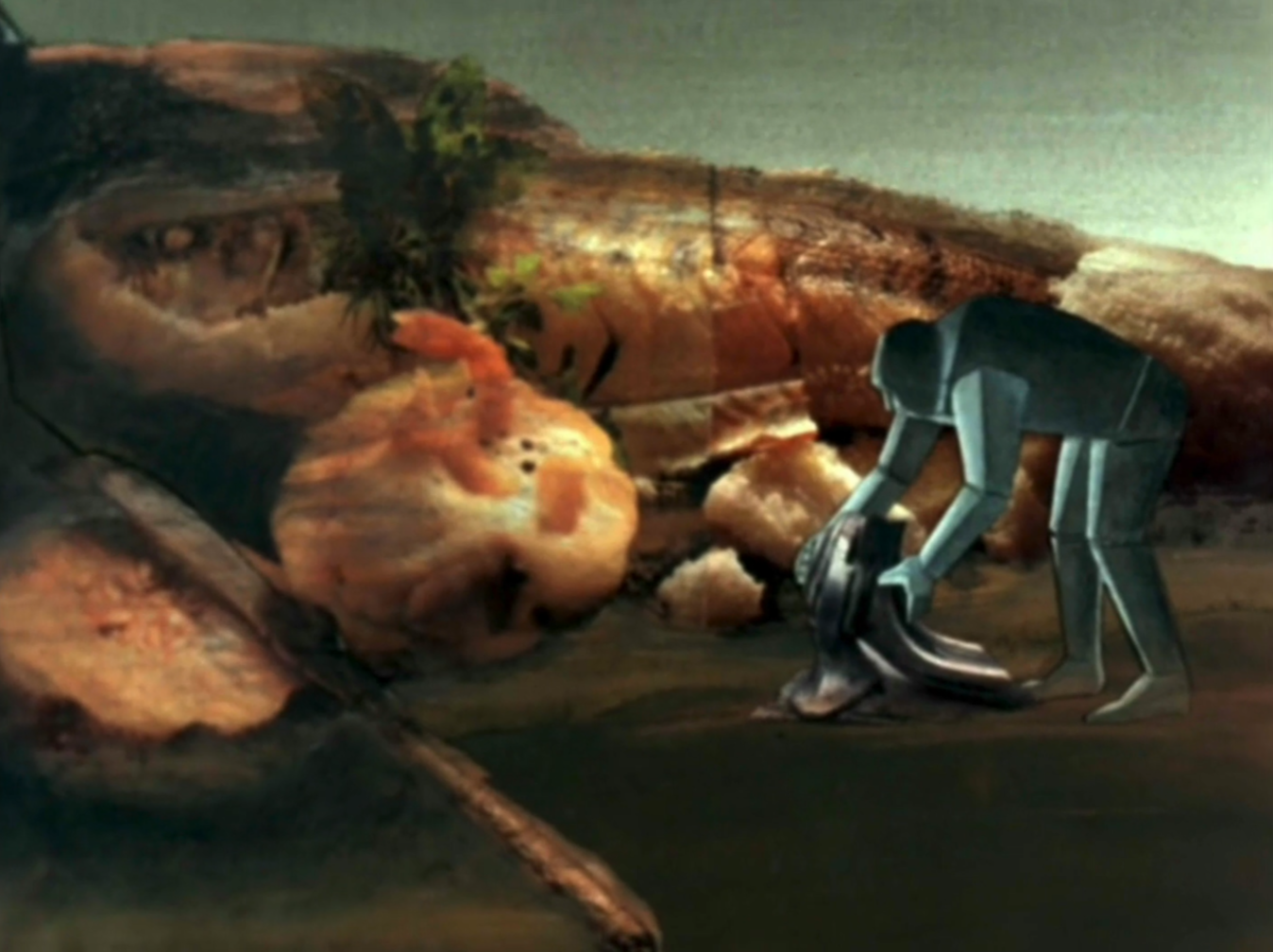

from Cave of Hercules, 1990. Dammbeck collages an idealized figure with cut-out elements of drawing, sculpture and anatomy

Hannah Höch, Lustige Person, 1932. Höch also liked to piece together figures from fashion magazines and sculptural images.

collage from Hercules Concept, the large, multimedia, amorphous body of work that includes Dammbeck’s physical and media collages, installation elements, and his documentaries.

Hannah Höch, Modenschau,1925-35

collage from Hercules Concept, 1980s

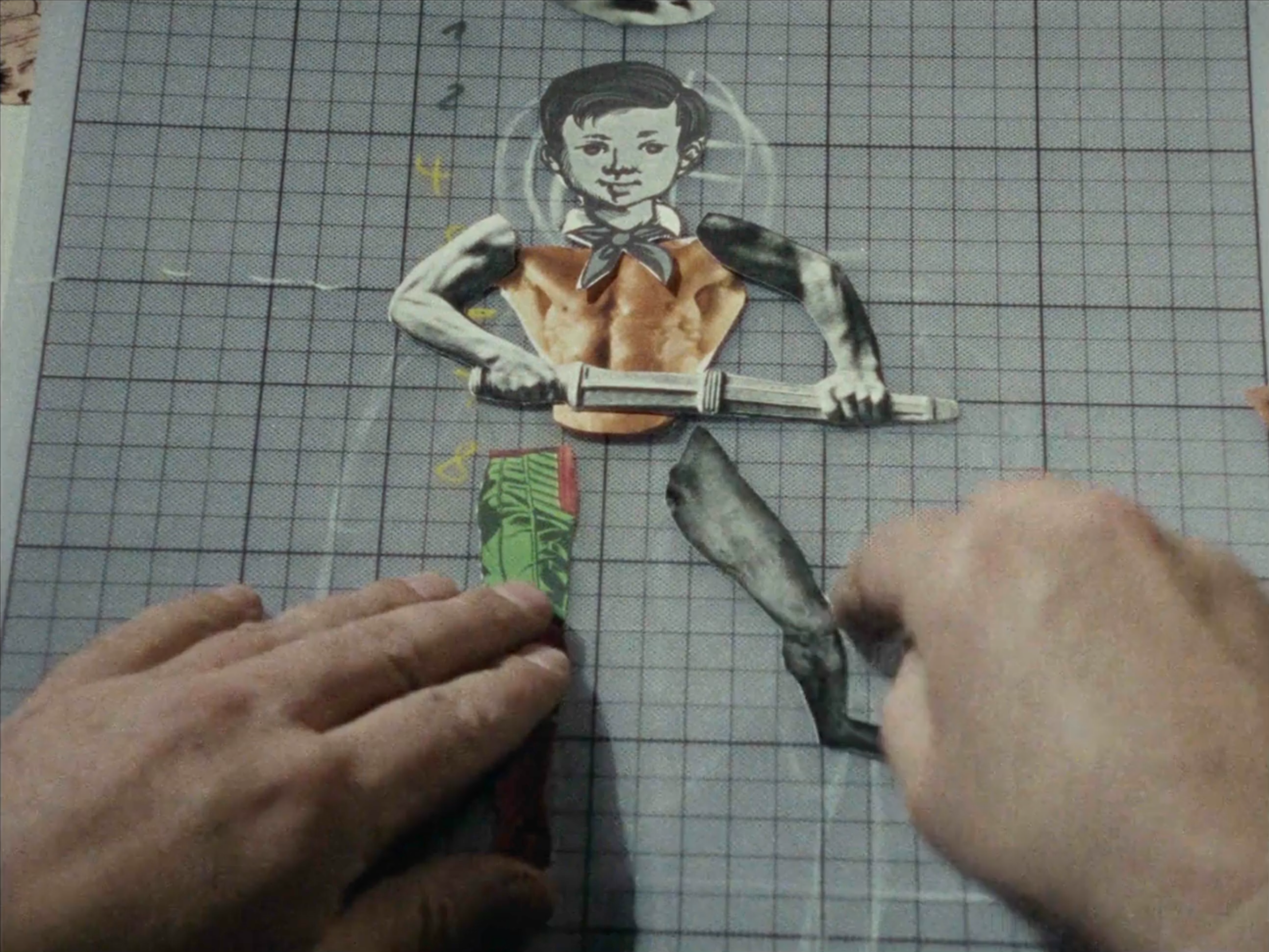

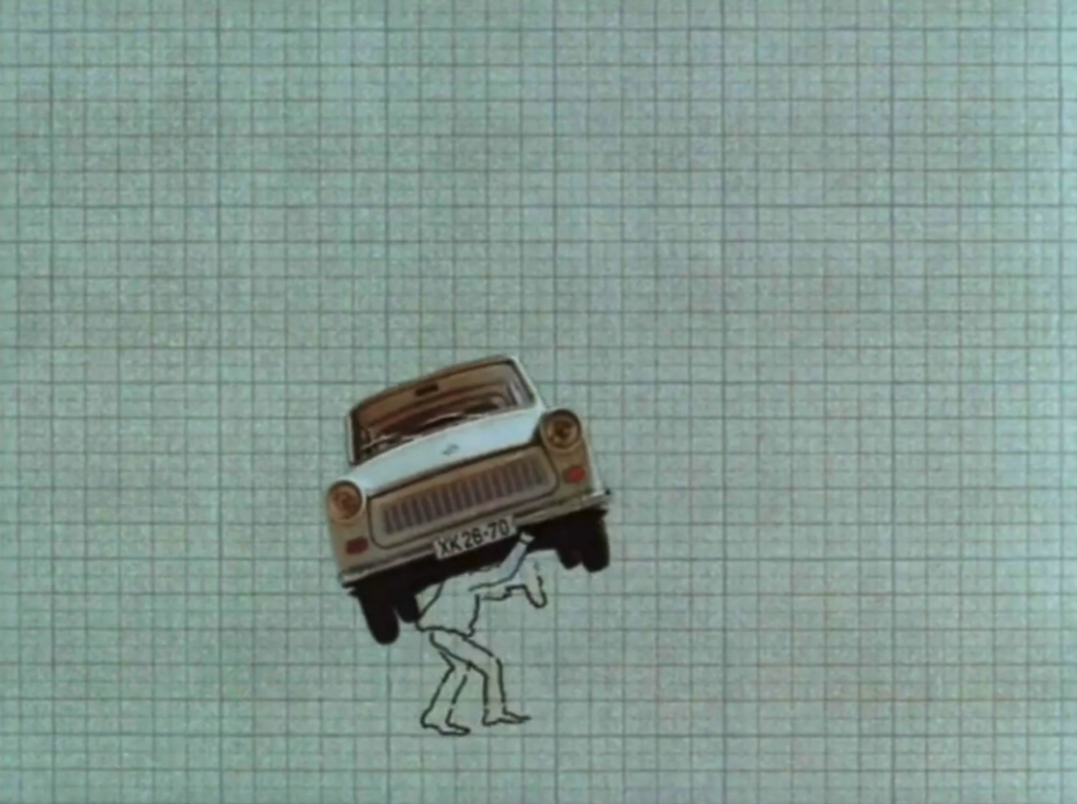

His animations hinted at this interest in collage. Live! (Libe!) (1978), animates the life of a man, drawn simply with lines on graph paper, but frequently includes photographs of more complex objects that would be difficult to animate. Later, in The Flood (Die Flut) (1986), cut-outs from culinary and automobile magazines are collaged together with classical busts in the piles of junk that the characters need to dig through to build a boat and escape the impending flood.

from The Flood, 1986. A character collects car parts to form his boat while the landscape appears to be made of a seafood dinner.

from Live!, 1978. A simply drawn man carries his fully-rendered car.

from the Flood, 1986. Piles of junk strewn across the island are made up of Grecian sculpture, car parts, and delicious meals

His short, Metamorphoses I (1978), shows his willingness to experiment with the medium as he draws directly onto or scratches into film, a technique known as non-camera or drawn-on-film animation.

This film was originally created for an multimedia exhibition called Tangents 1 (Tangenten I), the precursor to the First Leipzig Autumn Salon that was quickly banned for being too subversive. Despite its experimental nature, Metamorphoses was still allowed to be shown publicly.

from Metamorphoses I, 1978. Figures are painted directly onto film of a train speeding past buildings

In my post Filmmaking as Collage I describe the simple act of cutting between images in film as collage. Dammbeck takes this idea and pushes it to its limit in Hommage to La Sarraz (1981). Metamorphoses has its animations cut between or drawn on top of footage of Dammbeck and his friends taking a train through East Germany.

from Hommage to La Sarraz, 1981. Film of a man’s faced is scratched onto

Hommage expands on this and cuts between images of the artist and his friends and family, clips from contemporary TV shows, archival footage of Nazi propaganda, shots of the artist painting inky black paint over his studio window, strange stop-motion animations and stills of book pages. The bits of film are all manipulated, either presented in their negative form or drawn on directly in that same inky black.

Dammbeck describes this change in his own (translated) words on his website (specifically from the section on media collages).”Since the end of the 1970s, the sewing of painting canvas, photo canvas and papers with needles and coarse hemp threads and the sticking of the pictures together has now become an assembly with light, texts, music, action, film and slide projections.” Truly, filmmaking as collage.

from The Cave of Hercules, (1990). Combining the old and the new, the seams of Dammbeck’s physically stitched collage reveal the static of a CRT TV.

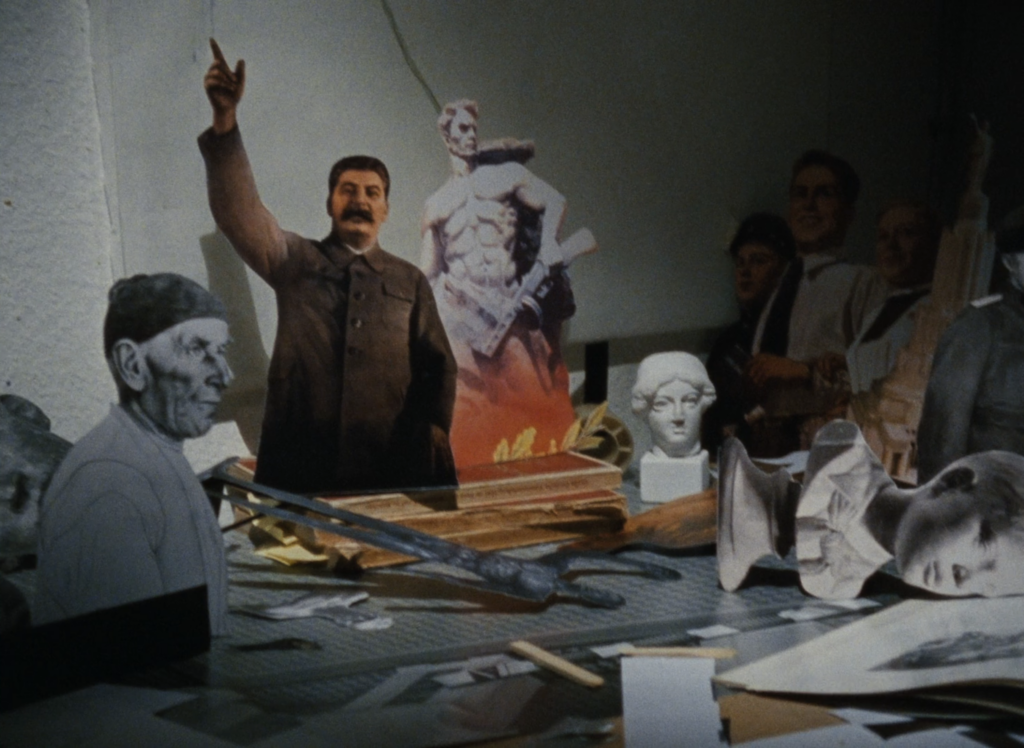

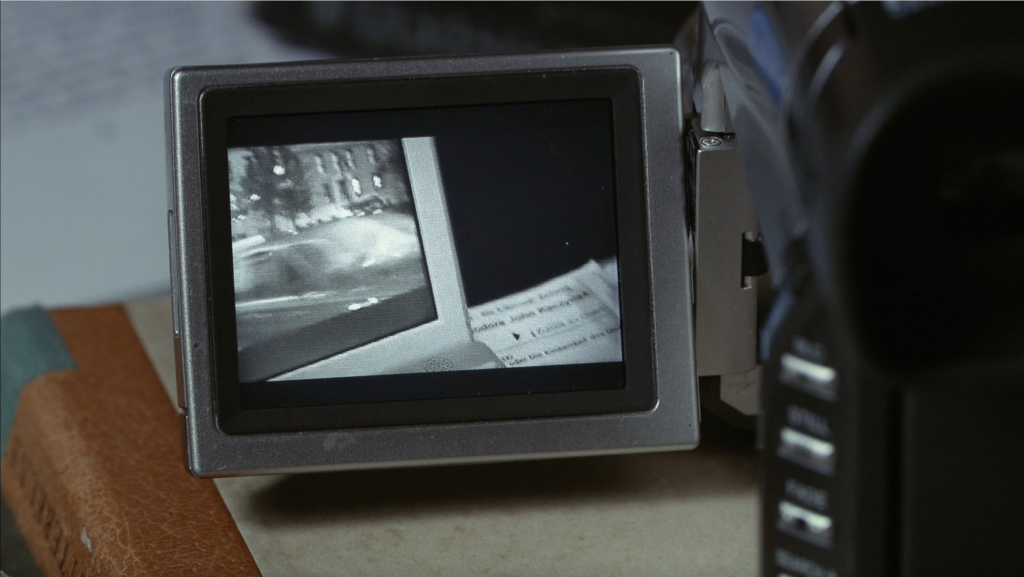

Though less visually experimental, even Dammbeck’s newer documentary works contain elements of collage. Clips don’t just play, cutting from one topic to another while a narration provides context, as with most documentaries. Instead, Dammbeck shows clips by recording the screen of digital and VHS camcorders or his MacBook. Rather than just showing still images to illustrate his point, he physically flips through lithographs and reproductive prints, turns pages of history and sociology books and thumbs through stacks of archival material. He does tie these disparate elements together with a typical (though academically dense) narration, but he also weaves throughout the films the poetic language of fairy tales and plays.

from Dürer’s Heirs, 1996. Cut-outs of famous figures, photographs, a sculptures are used throughout the film to illustrate historical events and political changes.

from Overgames, 2017. A screen within a screen within a screen. Dammbeck films the screen of a camcorder while it plays a panning shot of his Macbook, which in turn plays archival footage

from Dürer’s Heirs, 1996. Dammbeck uses projection to make interesting visuals that speak to the connection of these two art forms

When I tried to contextualize Lutz Dammbeck, I thought to go back first to Dürer, just as the Nazi and Soviet regimes did when the sought the new German art. Rather than fit into the classical canon, Dammbeck has formed his own German art canon through his documentaries. But it would be limiting to place him just within the context of German art. Because of his German heritage, he is keenly aware of the deceptive nature of fascist ideologies and uses his collage work to tear away the paper and reveal the “secret continuity of totalitarian structures.” But he’s also just an artist. Like Jim Henson, he’s curious, fascinated with his craft, and interested in experimenting and expanding until he literally can’t anymore.

from Drums West, 1961. When the animation ends, the camera pulls back and reveals Henson’s process for the film.

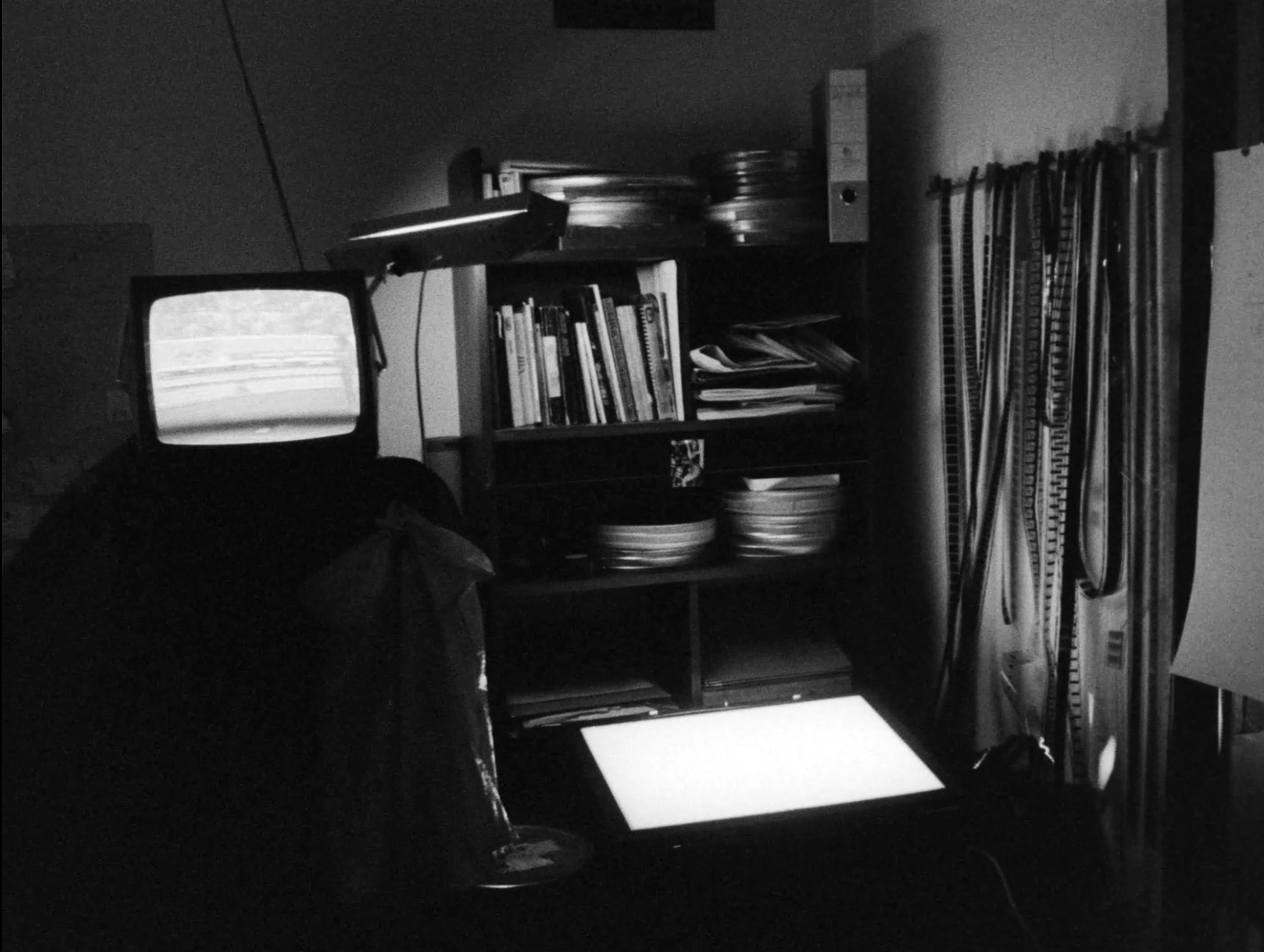

from Hommage to La Sarraz. (19xx). After the film, Dammbeck also chooses to pull back the camera and reveal his tools: a light box, reels of film, and CRT with never-ending scanlines.

Nearly Dammbeck’s entire body of filmic work is available on Kanopy, courtesy of the DEFA Film Library, which has since reformed to provide access to East German films and artists’ work. I highly recommend digging into Dammbeck’s delightful documentaries that explore his personal, national and international histories (listed below). His animations are beautifully surreal and include Herzog Ernst (Duke Ernest) (1984) and the collection titled Against the Mainstream. Dammbeck’s media collages truly fill me with envy and include Hommage to La Sarraz (1981), REALFilm (1986) and The Cave of Hercules (1990). Check out this strange, enigmatic artist today!

First Leipzig Autumn Salon: A Secret East German Art Exhibition, 1984

The Painter Came from a Foreign Land: East German Artists on Creating New Work in West Germany, 1988

Time of the Gods: The Life and Work of the German Sculptor Arno Breker, 1992

Dürer’s Heirs: An Insightful Picture of Early East German Art History,1996

The Master Game (Das Meisterspiel): An Art Mystery, 1998

The Net: Ted Kaczynski, the CIA, and the History of Cyberspace, 2003

Overgames: Game Shows and Their Impact on Human Behavior, 2015

Make it your New Year’s resolution to explore more film, and come join us January 2 at 7 p.m.

Information was primarily sourced from Dammbeck’s own words from his documentaries and website. The DEFA Film Library also provided basic timelines and context. Bits on Jim Henson were informed by his biography written by Brians Jay Jones, which is available in our collection.